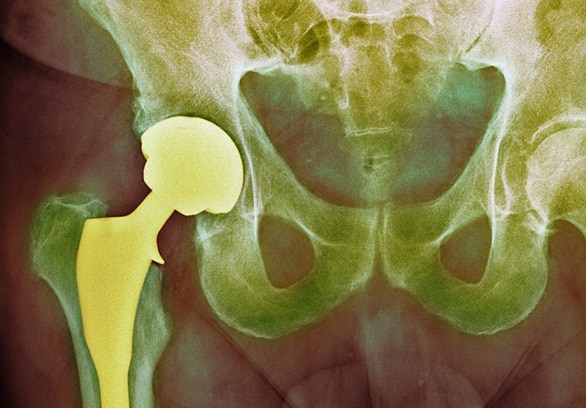

An artificial hip, like a natural hip, has two parts: a ball and a socket. These artificial parts are known as prostheses.

The ball, which replaces the rounded head of the femur (thigh bone), fits into a bowl-shaped socket in the pelvis called the acetabulum. In a total hip replacement, the ball of the femur and the socket in the pelvis are replaced with prostheses.

How the prosthesis is selected

There are many different types and brands of hip replacement prostheses available in Australia. The prosthesis selected for you may depend on your age, lifestyle, anatomy and the preference of your surgeon.

Surgeons choose prostheses with the aim of giving you the best result for the longest time. They generally also use a prosthesis they've had a lot of experience with and are comfortable using. Talk to your surgeon about the different types and why the one they’re recommending is best for you.

The Australian Orthopaedic Association National Joint Replacement Registry records the safety and effectiveness of all hip replacement prostheses used in Australia. You can check if the prosthesis your surgeon is planning to use is associated with a higher than normal rate of ‘revision’ (when a surgery has to be redone because of complications).

The components

An artificial hip is made of two components:

- Femoral component: a stem that fits and is locked into the inside of the thigh bone and an artificial ball which attaches to the stem and replaces the natural ball of the femur

- Acetabular component: an artificial socket that the ball of the femoral component fits into.

The femoral component

The femoral component is made up of the femoral stem and the artificial ball (femoral head) that connects to it. There are two parts to the stem: the section that fits inside your thigh bone and the section which extends outside. This is called the neck of the stem. The femoral head connects to the neck.

There are two main categories of femoral stem, based on how the stem is fixed to the inside of your thigh bone:

- A cemented stem, where a special material called bone cement sets hard, locking the stem in place.

- A cementless stem, where the stem is designed to wedge tightly into your thigh bone. The surface of this type of stem is designed to allow the thigh bone to form new bone that quickly grows around and into the roughened surface of the stem, further strengthening the connection of the stem to the inside of the thigh bone. Bone cement isn’t used.

Femoral stems are made of metal. The metal used is in part dependent on how the stem is attached to the inside of the thigh bone. Some cementless stems also have a special biologically active coating (hydroxyapatite) on the surfaces in contact with the thigh bone. This coating is thought to help the cementless stem bond with the bone.

The femoral head that connects to the neck of the stem is usually made of highly polished metal or ceramic. These materials ensure the surface of the ball is as smooth as possible, reducing friction and wear.

The acetabular component

There are also two main categories of acetabular component which are also based on how the component is fixed to bone. The acetabular component can be fixed into place using either bone cement or, more commonly, cementless fixation.

A cemented cup, or cemented acetabular component, is usually made entirely of plastic. The inner surface of the cup is perfectly shaped to fit the new femoral head.

A cementless acetabular component is made up of two parts:

- A metal shell that wedges tightly into the reshaped natural socket and allows new bone to quickly form and grow into its outer surface. Some shells also have a hydroxyapatite coating on the outside (or bone surface) of the shell to help bonding with the bone.

- A liner that is fitted and locked into the shell. The inner surface of the liner is shaped to fit the new femoral head. The liner is often called an acetabular insert and is usually made of plastic or ceramic.

What type of prosthesis will give me the best result?

There are many types of prostheses. They each vary slightly in design and the materials they’re made from and have advantages and disadvantages. It's important that you're aware of these options.

Methods of fixing to the bone

Both the femoral and acetabular components may be either cemented or cementless. It’s possible to have different combinations of cementless and cemented components in a hip replacement.

- A cementless hip replacement is when both the components are cementless. This is the most common combination, it’s currently used in over 60% of patients.

- Hybrid fixation is when the femoral component is cemented and the acetabular component is cementless. This is currently used in just over 30% of patients.

- A cemented hip replacement is when both components are cemented. Currently this method is used in just under 4% of patients.

- A reverse hybrid combination is where the femoral component is cementless and the acetabular component is cemented. It’s rarely used.

The use of cementless fixation has increased in recent years; hybrid and cemented fixation are used less.

Benefits: Whichever method is used, the results can be excellent for most patients. In general, cementless hip replacement has similar results in people younger than 75 years old.

For older people, cementing the femoral stem in combination with either a cementless or cemented acetabular component (hybrid or cemented hip replacements) can be better. This is because the success of cementless fixation, particularly of the femoral component, is dependent on the quality and strength of the surrounding thigh bone. As people (particularly women) get older, bone quality and strength tend to lessen.

Materials used

In the past, the main reason hip replacements needed to be redone was because the bearing surfaces (where the two moving parts of your artificial hip join together) wore out. The materials from which these surfaces are made can affect the durability of the prosthesis.

When the surfaces wear, very small particles of the material used are released. If enough particles are released, your body can react. This means the bone and other tissues around the joint may become inflamed and the components can become loose within the bone. If this happens, your hip replacement can become painful, particularly when you walk. If this is a major problem, the joint surface and loose components may need to be replaced.

There are three main bearing surface combinations:

- metal on plastic

- ceramic on plastic

- ceramic on ceramic.

Fortunately, over the past 15 years, the quality of the materials used have improved significantly. The most commonly-used plastic (cross-linked polyethylene) is much better than before, as is the ceramic (mixed ceramic). The quality of the metal and smoothness of the surface of metal femoral heads have also improved. This means you’re now less likely to need repeat surgery due to wearing of the bearing surface.

Non-standard prostheses

There is a range of non-standard femoral and acetabular components which are used for specific reasons. Here are some examples:

Non-standard femoral components

- Exchangable neck prostheses: This type of femoral stem has two parts: the section of the stem that fits inside the thigh bone and the section which extends outside. They’re put together when the stem is in position.

Benefits: An exchangeable neck enables your surgeon to slightly vary the position of the head after the stem has been positioned to fit your needs. This isn’t possible if the neck and stem are in one piece.

Risks: Exchangeable necks are associated with higher failure rates.

- Mini stem prostheses: A mini stem is a very short femoral stem which is fixed into the top of the femur, unlike the standard femoral stem that extends almost halfway down the femur. Mini stems are a relatively new technology and aren’t commonly used.

Non-standard acetabular components

- Constrained acetabular component: Unlike a standard acetabular component, this has a locking mechanism which holds the femoral head in the socket. The standard acetabular component doesn’t have this mechanism because the femoral head is usually prevented from coming out of the socket (dislocating) by surrounding muscles and tissues.

Benefits: Surgeons usually use this device when they believe there is a higher chance of dislocation. This device works best in older people (aged 70+).

Risks: They’re not used routinely because they may increase the rate of loosening, particularly of the acetabular component. In younger or more active patients the revision rate is 4 times higher than in older people.

- Dual mobility acetabular component: A dual mobility acetabular prosthesis has an insert that fits snugly into the acetabular component but unlike a normal insert it isn’t fixed to the acetabular component and can move a little as your hip moves.

Benefits: The range of movement is greater than single mobility prostheses, which may benefit some patients. But it’s mainly used to reduce the risk of dislocation.

Risks: The insert can wear more because it has two sides that are moving rather than the usual one. Increasing wear also increases the risk of the prosthesis becoming loose. This is a relatively new prosthesis design so the long-term results aren’t yet available. At 5 years, there's no difference in the revision rate of dual mobility prostheses compared to standard prostheses.

Cost

The prosthesis won’t normally cost you anything. If you have private health insurance, your health fund pays. If you’re a public patient, Medicare pays.

HCF funds prostheses listed on the Federal Government’s approved prostheses list. All of these devices have been approved for use by the Australian regulator of medical devices (Therapeutic Goods Administration) as well as a special body in the Department of Health (the Prostheses List Advisory Committee).

This body recommends which hip prosthesis should be added to list after seeking advice from the Hip Prostheses Clinical Advisory Group. This group includes orthopaedic surgeons who are experts in hip replacement.