How nanotechnology is revolutionising medicine

Australia is leading the world in the miniaturisation of medical devices that will transform medical treatment.

Health Agenda magazine

May 2017

To the naked eye, the little square of silicon looks smaller than a standard postage stamp and only slightly more interesting. The modest Nanopatch, designed in Australia, doesn’t look like something that might revolutionise our fight against infectious diseases. But it’s what you can’t see that matters in the field of nanotechnology.

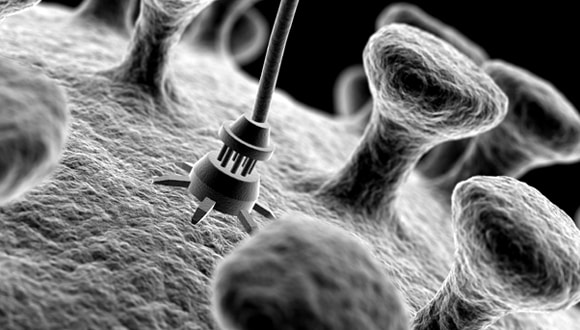

Under the microscope, thousands of infinitesimal spiky projections appear on the one-square-centimetre patch. When pressed painlessly to the skin, each of those micro-projections works with the body’s immune system to rapidly release vaccines where they’re needed most, offering a painless, low-cost means of countering illness.

This needle-free method for delivering vaccines is just one way that nanotechnology promises to change medicine. It offers faster and more accurate diagnosis and treatment of disease, superior imaging technology, the ability to deliver drugs directly into a cancerous tumour, or to load particles far smaller than the width of a hair with the medications to treat Parkinson’s disease or progressive deafness.

New toolbox

Human trials of nanotech are already underway. Nanopatch creator Professor Mark Kendall, from the Australian Institute for Bioengineering and Nanotechnology at the University of Queensland, says the device averts needlestick injuries and can reduce the millions of deaths a year from infectious diseases.

Working at the nanoscale – a nanometre is one-billionth of a metre – opens a new toolbox for delivering medicine at the right dose, right place and right time, says Professor Kendall. Delivering treatment via a patch is an improvement over needles in multiple ways.

The 20% of the population with a needle phobia can relax. Using a dry vaccine also cuts the need for refrigeration, which is an issue in developing countries. Its targeted application means you can use less vaccine, so it’s cheaper, and in an epidemic, people can self-vaccinate with practically no risk.

“Nanomedicine is the embodiment of genuine personalised medicine with diagnosis and treatment on an individual basis as opposed to things being done through massive clinical trials,” he says.

Local leadership

Australian scientists are leading the way in this revolutionary field. In September 2016, chemists, engineers and medical researchers from the University of New South Wales (UNSW) published results of a study in Nature Nanotechnology showing that shape and size matter. Rod-shaped and worm-like polymer nanoparticles were more effective at delivering drugs directly into the nucleus of a cancer cell than other shapes, offering the potential of improved treatment.

Lead researcher Scientia Professor Justin Gooding, co-director of the Australian Centre for NanoMedicine, says the discovery means scientists can target drugs to where they’re needed, leading to more effective treatments with lower dosages and fewer side effects.

“The impact for the field is huge,” Professor Gooding says. “At the moment you take a pill and hope that some of the drug goes where you need it to go, but now we can develop materials that deliver drugs where we want, when we want and have the drugs go virtually nowhere else.”

Reducing the side effects of cancer treatments such as chemotherapy – which effectively works by poisoning the body – would offer not only more effective treatment but better quality of life during that treatment, he adds.

His UNSW research group, which is part of the ARC Centre of Excellence in Convergent Bio-Nano Science and Technology, is also developing nanoparticles to assist in the early detection of diseases. Such work includes ultrasensitive biosensors, which can penetrate into parts of the body that normal sensors can’t reach and potentially find microscopic reservoirs of diseases, such as HIV, that can lurk undetected, evading medication.

Separately, scientists around the world are also applying nanotechnology in the field of regenerative medicine, to encourage cells to regrow and regenerate tissues such as heart valves.

Small challenges

Building components on the nanoscale allows scientists to take advantage of physical, chemical and biological interactions that aren’t possible on a larger scale, but working with minute matter presents its own special set of challenges.

“You can’t see nano things. The smallest thing you can see with a microscope is 200 nanometres or so, and most of these particles are much smaller than that,” says Professor Gooding. “In nanotechnology, half the challenge is making it, the other half is proving you’ve made what you think you’ve made.”

Funded by the Heart Foundation, Australian researchers have recently created nanoparticles that target the activated platelets that form blood clots and lead to heart attacks and strokes. They deliver a clotbusting drug right where and when it’s needed. Similar work is underway to deliver drugs to the hard-to-reach inner ear, to counteract progressive deafness.

Cost effective

Treating diseases at such an ultra-small scale will come at a fraction of the cost of conventional medicines, predicts Dr Angus Johnston, a senior lecturer at the Monash Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences. The prohibitive cost of antibody therapies being trialled for Alzheimer’s disease, for example, puts them beyond the reach of most people. Delivering such drugs inside nanoparticles directly to where they’re needed reduces the dose and cost.

“If we can make nanoparticles deliver drugs [in the body] effectively, we basically cut the price by 100 times,” Dr Johnston says.

Bright future

The technology involved in nanomedicine is similar to that being used to create better and brighter colours in the latest TVs, Dr Johnston says. Unsurprisingly, it’s also coming into the sphere of medical imaging, delivering crystal-clear diagnostic screens, which can allow doctors to diagnose even at a distance.

Nanotechnology has applications across chemistry, biology, physics, materials science and engineering, covering everything from wrinkle-resistant fabrics to better baseball bats and batteries with improved energy storage capacity.

But it’s in the healthcare field that nanotechnology promises to provide the biggest results. Dr Johnston says he believes that “in 20 years’ time most drugs will be delivered by some nanotechnology-based delivery system, getting drugs to where they need to go without side effects.

“The diseases you can treat are almost endless in terms of these kinds of therapies. You can basically have a vaccine against almost any disease.”